Good Friday.A.20

The Rev. Melanie McCarley

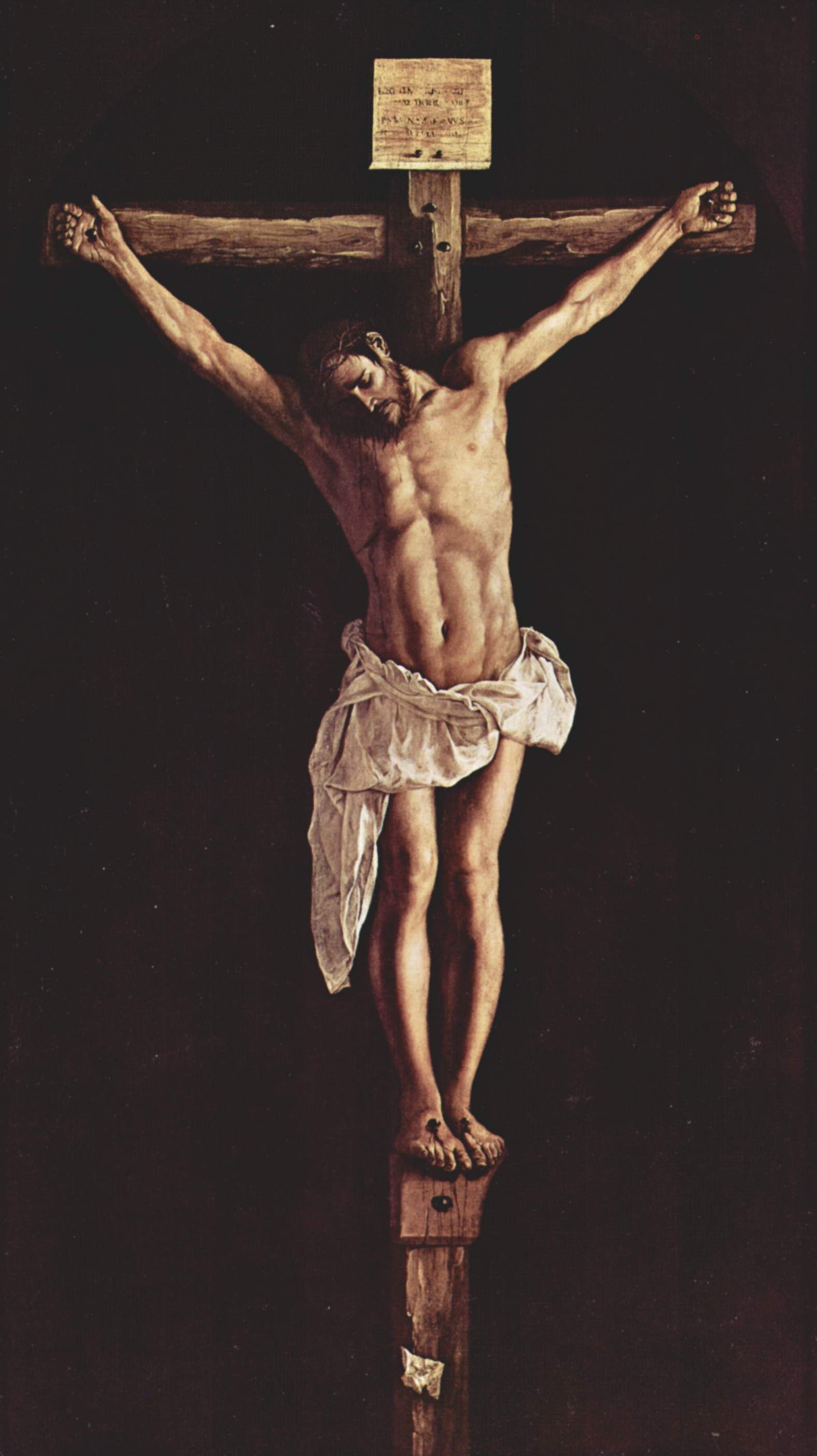

The British novelist and playwright, William Golding once wrote: “The crucifixion should never be depicted. It is a horror to be veiled.” This would come as surprising news to Christians of the Middle Ages who went to great pains to depict the agony of the crucifixion of our Lord, employing copious amounts of blood, sweat and tears to convey the extent of our Savior’s suffering. Crucifixes—they’re painful and difficult to behold. It’s a darn sight easier to turn our head from them than to gaze upon a suffering Savior.

As a general rule of thumb, though by no means hard and fast, Crucifixes are the primary domain of the Westernized Roman Catholic Church; The Christus Rex—the image of the resurrected Christ, depicted in splendid robes, wearing a crown and looking very much alive belongs to the Eastern Orthodox Church. The naked cross is decidedly Protestant. Episcopalians and Anglicans—well, you’ll see all three, depending on where you happen to be worshipping. But today—this afternoon, I would like to talk about the crucifix—what it signifies and how it extends hope to you and me during the troubled time in which we live.

A lesson on history as relates to the cross has stayed with me for many years. The crucifix (in particular, bloody, agonizing crucifixes) gained in popularity as the Black Death was ravaging Europe during the Middle Ages. If you think about it, this makes perfect sense. People were dying at alarming rates. The world as people knew it, was ending. There was great fear and panic and scientific understanding as we know it today simply did not exist. People wondered where God might be in the midst of all this suffering? Why, people asked, would one person die of the plague, and not another? No one seemed safe. People of all classes, races and backgrounds were afflicted. You, or the people you loved could be perfectly well today and dead in just a few days time. Does any of this sound familiar?

And so, bloody, agonizing crucifixes gained in popularity. Why? Why should a crucifix be the symbol of choice? Why not focus on the outcome—the resurrection, the victory? Why should our brothers and sisters of the Middle Ages and many Christians ever since, choose to focus on the most painful moment of our Savior’s life? Here’s my guess. Because in a way that their Eastern counterparts, who were largely unafflicted by the plague could not understand, the people of this time found comfort in the suffering of Christ. Comfort, and even hope. Hope in the cross. Because, if you look at that crucifix, you see a depiction of God who knows what it is like to suffer as you are suffering. You look at that cross and see a God with whom you can identify. You see a God who knows what it is like to be you, frightened, in pain and knowing that death is near at hand.

And that fact, in the midst of what our world is going through right now, is worth holding on to. The God we worship is not high and remote. Our Savior is not untouched by human cruelty and barbarity. Jesus endures suffering—and, remarkably, miraculously, transforms that pain and anguish into victory. His suffering isn’t pointless; it is active and redemptive. In a world in which suffering, pain and grief are very real—this is a God in whom those who know what it is to suffer, can relate. This is a God in whom suffering people can place their trust.

There are some who look at the pain and horror of the world: mass shootings, airplane crashes, earthquakes and storms of devastating proportions, cancer, car crashes and terrorist attacks –and our current world-wide pandemic and respond with something akin to “It must be the will of God.” But I say to you, if this (if any of this) is the will of God, then that God is not the type of deity whom I am comfortable worshiping.

George Buttrick, former chaplain at Harvard, recalls that students would come into his office, plop down on a chair and declare, “I don’t believe in God.” Buttrick would issue this disarming reply. “Sit down and tell me what kind of God you don’t believe in. I probably don’t believe in that God either.”

Think of it this way. The horrors of this world are bearable, not because we are able to pretend with pious pomposity that they do not exist. The horrors of the world are bearable because we believe in a God who knows precisely how horrible they are.

What kind of God is it that we worship? In many ways, particularly on this day, ours is the Crucified God. And this, I suggest to you, is Good News. Frederick Buechner, in writing of the cross states: “A six pointed star, a crescent moon, a lotus—the symbols of other religions suggest beauty and light. The symbol of Christianity is an instrument of death. It suggests, at the very least, hope. That cross whether it carries upon it the bloody body of our suffering savior, the risen Christ of the resurrection or is pointedly bare—that cross forms a connection, a bridge between humanity and divinity, one which carries us across the divide of sin and death to life, immortality and peace.

The Christian theologian Philip Yancey writes: “Any discussion of how pain and suffering fit into God’s scheme ultimately leads back to the cross.” That’s true, as I see it. It is as true and hopeful a statement as can be made. This day, we behold a crucified Christ who lived and died in solidarity with creation. But Good Friday is not where we stay. For ultimately, we are not people who define ourselves by Good Friday; we are an Easter people, people of the resurrection. But in order for us to get to glory of Easter Morning, we must first walk through the agony of Good Friday—with the knowledge that God suffers in solidarity alongside us. And because of that, the promise of Easter is made all the more precious for those who believe in his grace. In the name of the crucified and risen Savior. Amen.