Proper 23.C.25

Psalm 111

Melanie L. McCarley

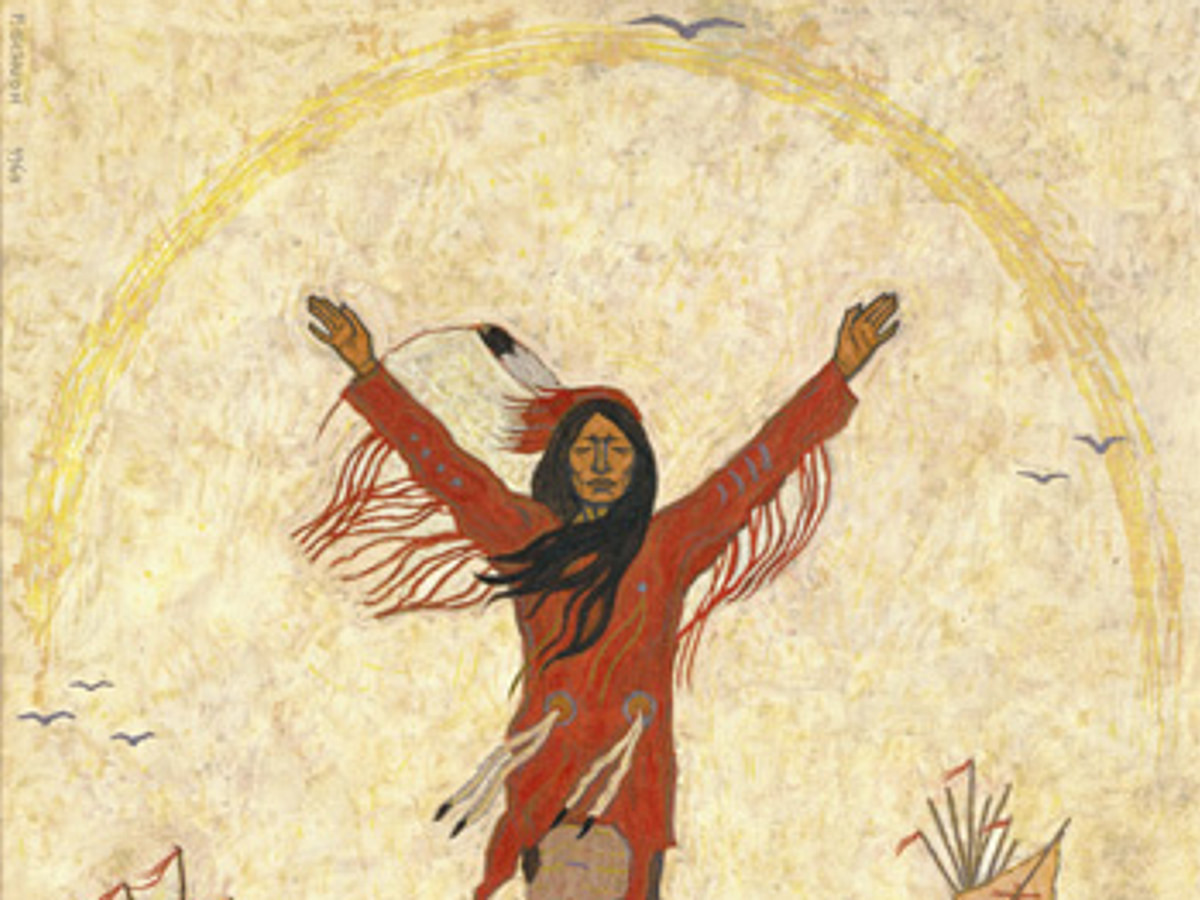

A few years ago I took a sabbatical to the Southwest. While there, I learned that The Dine (known to many of us as the Navajo Nation) teach their children a lesson about the morning sun. From this perspective each sun is brand new and will not return. Therefore, each day should be lived well so that the sun’s precious time is not wasted. Dine tradition holds that at sunrise the sun should be greeted. This is done by opening the door of one’s home and making an offering of a pinch of white corn pollen (a sacred substance representing life, purity, happiness and prosperity). If you are feeling up to it—you can run toward the sun to make your offering. It is, I believe, a hopeful and joyful tradition. I believe the author of Psalm 111, which we recited this morning, would agree.

Psalm 111 begins with a greeting as well “Hallelujah!” which is a word constructed of the Hebrew words Hallel (meaning praise) and yah ( which is a shortened version of Yahweh) meaning God. In short, Hallelujah, means “Praise God!” It’s a fine beginning not only to a psalm, but also to a new day.

There’s a great deal we can learn from Indigenous Peoples as well as from our forebears in the Holy Land. Not leastwise is the concept of Wisdom.

Unlike many psalms, whose concluding verse is more or less a repeat of the first verse, the Psalmist here does something different. Instead, what we find is a nod toward the Wisdom literature in the Old Testament. In the last verse of Psalm 111 the Psalmist points to that verse which sums up the Book of Proverbs: “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.” The first thing is to understand that “fear” in the last line of Psalm 111 is not fright or terror but reverential awe—the kind of feeling that you have when you stand before something well and truly great.

In the Bible, Wisdom is differentiated from Knowledge. Think of knowledge as the kind of knowing that we can gain in a classroom. Here we come to understand facts of human history, the biology of cells, chemistry, arithmetic, etcetera. This kind of knowledge is often referred to as “Book Smarts” (and make no mistake, it is important). Wisdom, however, is the kind of knowing that we pick up as we bump along in life. Wisdom is based upon the kind of knowledge that is gained through discernment. Discernment not only of what is best for me, as an individual, but best for everyone, including the environment of which we are called to be stewards.

For example, in the nineteenth century, our country saw the large-scale slaughter of American bison, driven by commercial hunting, government policy aimed at Native American subjugation and the expansion of railroads. It nearly led to the species extinction from an estimated 60 million to just a few hundred. Just because you can shoot a buffalo and earn money from doing so—doesn’t mean that it should be done. Building a profitable entertainment business based on aiming guns and shooting from train windows is knowledge without wisdom. Sadly, it’s the kind of response that has characterized much of our country’s relationships with Native Americans and nature since the colonists arrived.

During my time in the Southwest, I was fearful that I might find my Caucasian self to be met with hostility. There might have been some (I don’t know)—but what I found, more than this, was a sense of welcome and deep desire on behalf of native people’s for individuals such as myself to understand and appreciate their distinctive way of life which, in my estimation, is based largely upon a symbiotic relationship with nature that translates well into wisdom. The kind of wisdom that we find in many of the Psalms—ones which praise the mighty works of God and seek the guidance of the Lord. That’s something we would do well to seek to kindle in our own lives. It’s closely related to the theme of today’s Gospel lesson, when our Savior heals ten lepers, but only one returns to praise God with thanksgiving.

In Robin Wall Kimmerer’s exquisitely crafted book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, we have the pleasure of learning from a trained botanist and member of the Potawatomi Nation. She offers a different way of viewing the world than the one to which many of us have been accustomed. Kimmerer says: “the language scientists speak, however precise, is based on a profound error in grammar.” Frequently, when writing or speaking in a scientific text, non-human living beings are referred to as “it”. This reduces animals such as buffalos and plants such as trees to mere objects—and that fosters exploitation.

Instead, Kimmerer suggests that we learn the language of animacy, a language more heavily populated by verbs rather than nouns. Imagine how the feel of the world would change if we thought of things like trees not as objects but rather as dynamic sites through which the power of life continually unfolds. If we could speak of creation in this manner—would we still think of our world as a stockpile of resources or commodities waiting to be exploited? A “grammar of animacy” alerts us to the power of life pulsing through all things, knitting them into a vast, dynamic community of life. It is a way of speaking that draws us into the world, making it less likely that we will think of ourselves as separate from, or even masters over, others.

As we gather together on Indigenous People’s Day Weekend, it’s a good time to remember the gifts of knowledge and of wisdom. Today we have the knowledge of the facts of the history of our country, which brought untold suffering, death and destruction to so many indigenous peoples; and we have been graced with the hope that comes with Wisdom—a way of looking at our past with a greater understanding of what we can learn when discernment (aided with a large dollop of thanksgiving to God our Creator) is added to our understanding.

This brings us full circle to the Dine’s way of greeting the morning and the first line of Psalm 111. Both are based upon the concept of praise—of acknowledging the truth and beauty of that which is greater than ourselves. Both begin with awe—a fine lesson in humility—a good way to begin each day. I close with the words of the Psalmist “Halleluiah….God’s praise endures forever.” In the name of our risen Savior, Jesus Christ. Amen.