Proper22.A.2023

Philippians 3:4b-14

The Rev. Melanie L. McCarley

In his letter to the Church of Philippi, St. Paul writes: “I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the sharing of his sufferings by becoming like him in his death .” These are strong words—and, if you think about it, they are deeply startling as well. I find myself wondering how was heard in the community of Philippe and how well it would play out today for those who prefer to preach a gospel of wealth and success as opposed to one rooted in the saving grace of a suffering Christ. I suspect it might be something of a hard sell—because, let’s face it, a gospel of wealth and success, at least on the surface, sounds a good deal more appealing than the one preached by St. Paul. But the community of Philippi—they saved this letter—and my guess is, because they recognized truth when they heard it.

I wonder, how many of us would raise our hands if asked to partake in suffering? It seems to me that most of us take great pains to avoid suffering—and many, not only in the time of Jesus, but in our time as well, regard suffering as a failure of sorts—whether it is the result of poor decision making, bad luck, illness, disease or death. For many of us, suffering is only to be found hidden behind the countenance of a stiff upper lip and a response of “fine” or even “good” when inquiries are made.

For some, suffering results in anger and bitterness, a sense of isolation, self-recrimination and self-loathing. But for others, suffering has the opposite effect, that of opening the heart to others who are undergoing suffering of their own. In this case those acquainted with suffering are able to extend empathy and compassion to others. This is the kind of suffering which I believe Jesus exemplified on the cross—a suffering which gifts us with the ability to see, in the crucifixion of our Lord, God suffering in solidarity with us individually and with all of humanity. The crucified God is a God who knows what it means to suffer—yet, in this suffering God chooses to embrace the world rather than condemn it. The crucifixion is a picture of the redemptive nature of suffering; and this is what St. Paul is reflecting upon in his letter to the community of Philippi.

This brings to mind an event which took place on March 23, 1847 in the small town of Skullyville in Indian Territory. Major William Armstrong, the U.S. agent of the Choctaw Nation took the floor to speak to the community, one filled with tribal members, missionaries and traders. Armstrong, reading aloud from a pamphlet, informed those gathered about an event taking place on the far side of the Atlantic which many, if not most of us would assume held no obvious interest to the Choctaw people who had immense problems of their own. This event—none other than the Great Potato Famine in Ireland.

The historical record doesn’t reveal exactly what Armstrong said at the gathering, and so far no one has unearthed the pamphlet, distributed by the Memphis Irish Relief Committee. But the Choctaw people responded with remarkable generosity.

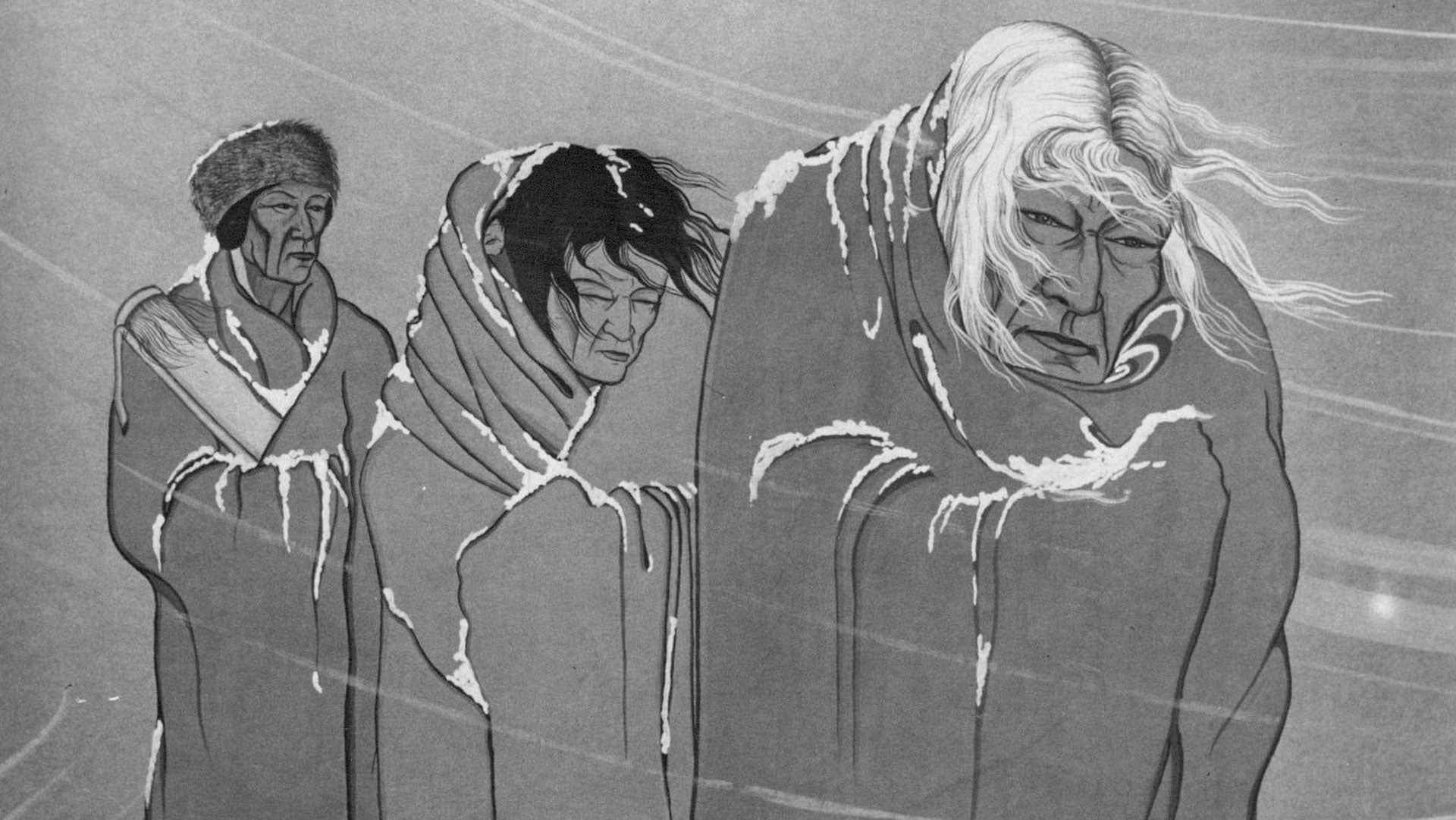

Bear in mind just a little over a decade before, the Choctaw people had been driven from their homes in a mid-winter march of hundreds of miles to Indian Territory. The French aristocrat and diplomat, Alex de Tocqueville witnessed this and wrote: “The Indians had their families with them; and they brought in their train the wounded and the sick, with children newly born and old men upon the verge of death. They possessed neither tents nor wagons, but only their arms and some provisions…. Never will that solemn spectacle fade from my remembrance.” Between 1831 and 1833 an estimated 15,000 Choctaw people traveled the Trail of Tears, a journey of more than 500 miles, and approximately a quarter of them died along the way.

The Choctaw, who had lost so much, and had so little, were deeply moved by the plight of the Irish. Some reportedly wept. Despite their own impoverished circumstances and the recent dispossession of their homelands, they raised the equivalent of more than $5,000 today to help with famine relief efforts for people an ocean away. It’s a remarkable expression of charity, from a people whom it is difficult to imagine could be less well positioned to act philanthropically. Don Mullan, an Irish humanitarian, writes: “The Choctaws had suffered horrendous brutality at the hands of white Europeans, and yet despite that they could allow their humanity to supersede any prejudice they were entitled to carry.” White Deer, a member of the Choctaw Nation says: “As I see it, you have one poor, dispossessed people reaching out to help another poor, dispossessed people …. We heard about another people who were suffering much as we had suffered, and so we must help them.” Today there is a close, reciprocal relationship between the Choctaw Nation and the people of Ireland, one born of suffering which found its response in compassion.

Christian theologian, Jurgen Moltmann, in his book, The Crucified God, poses the question: “What does it mean to recall the God who was crucified in a society whose official creed is optimism, and which is knee-deep in blood?” It’s a good question, and perhaps one way to gather a response is to delve more deeply into the history of our country, including the difficult and unpalatable parts of our history, and find therein examples of grace and compassion that we might emulate—making us a better and stronger people.

St. Paul writes: “I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the sharing of his sufferings by becoming like him in his death .” You may recall a particularly beautiful collect of the service of Morning Prayer which speaks of the suffering of Christ. It seems a particularly fitting way to conclude today’s sermon. It reads: “Lord Jesus Christ, you stretched out your arms of love on the hard wood of the cross that everyone might come within the reach of your saving embrace: So clothe us in your Spirit that we, reaching forth our hands in love, may bring those who do not know you to the knowledge and love of you; for the honor of your Name. Amen.

• From an article in Smithsonian, September/October 2023 “The unlikely, enduring friendship between Ireland and the Choctaw Nation by Richard Grant