Proper 24.A.20

Philippians 4:1-9

The Rev. Melanie McCarley

Have you ever been in one of those situations, where no matter what you said—you knew, without a doubt, that it was going to be the wrong thing? There are many such occasions in our lives, but for me, I think the women’s dressing room is one of the most treacherous places on earth. This is the arena where friendships are strained and familial relations are brought to the brink of disaster. The simple question: “So, what do you think?’ is fraught with land mines. One wrong word, and this relationship is going to be blown to smithereens.

Picture this. There you are, standing in Talbots (after all, this is New England) along with your best friend. Her only flaw is that she can be overly sensitive at times. Or, if you never find yourselves in these types of situations, picture yourself in a boardroom commenting on a friend’s proposal. You can say what you think—tactfully. Don’t you think a size larger would be better? Or, (for those in the conference room), “Don’t you think more research would help sell your point?” Or, you can play it safe and keep your mouth shut. Say nothing. Nod your head and commenting on the color—anything but the straining seams. Or simply say that all the punctuation looks to be in order. The point is, you are in what amounts to a very delicate situation.

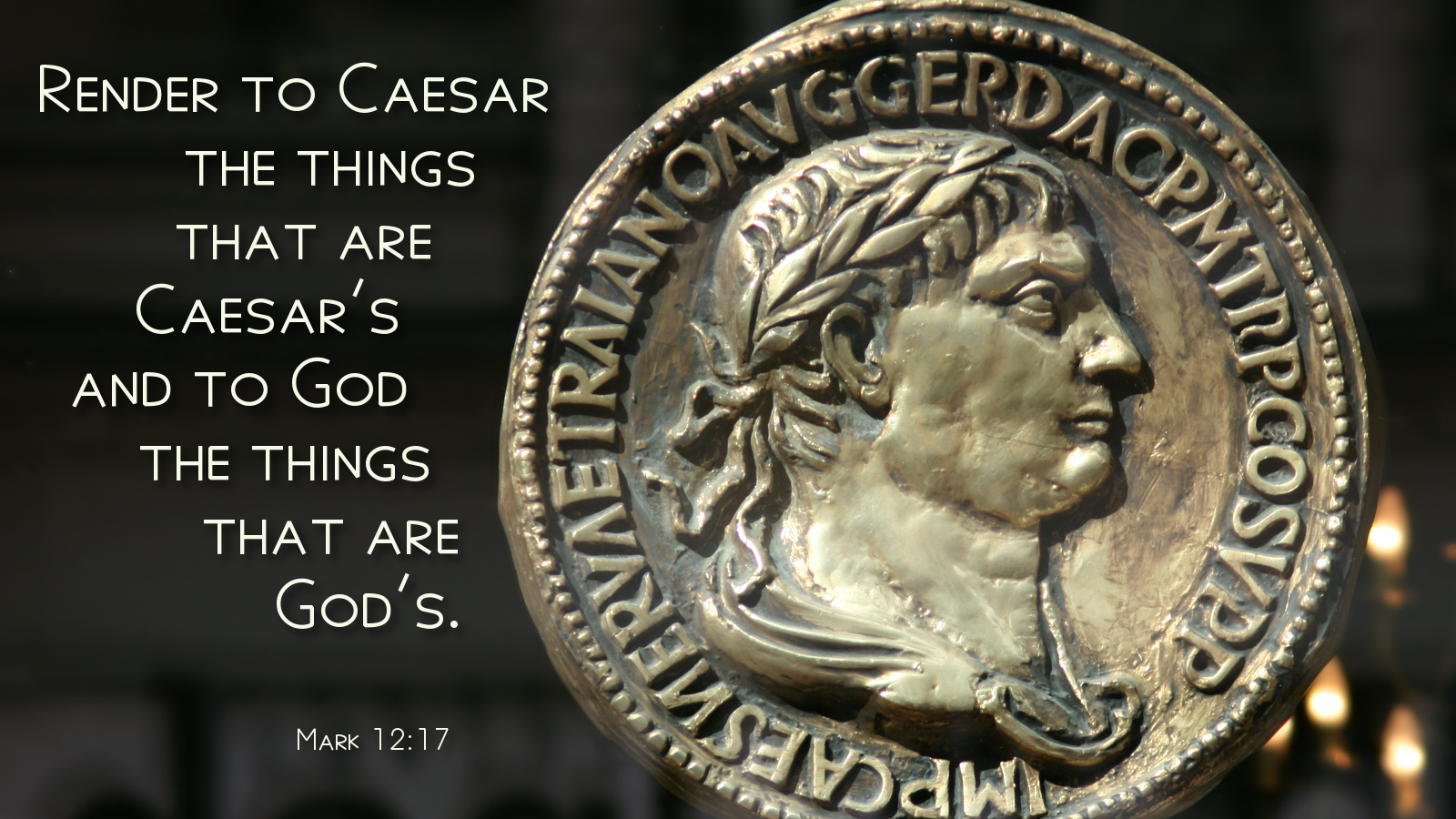

On one level, the encounter between Jesus and the Pharisees is meant to be amusing. Here we see Jesus cleverly outsmarting the Pharisees and the Herodians by some fancy mental footwork. “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” However, on another level, this situation is anything but funny. This was no ancient version of keystone cops. It was a carefully contrived plan to accuse Jesus of treason and do away with him. Let’s take a closer look.

First, we need to know who the Herodians were. They, like the Pharisees, were Jews. However, unlike the Pharisees, they were supporters of Herod Antipas (King Herod’s son), Rome’s puppet ruler and collaborator with the empire. Now, at first glance, it seems the Pharisees (who were opposed to the Roman occupation) would have nothing in common with the Herodians. This is true—but each group shared a mutual opposition to Jesus and were deeply concerned about the trouble he was stirring up among the people.

And so, the two groups collude and introduce their question with oily compliments. Their goal, to get Jesus to say that it’s lawful to pay taxes to the emperor. If he does this, he will offend the Pharisees, and, more importantly, the crowds who oppose the Roman occupation. On the other hand, if they can get Jesus to say that it is unlawful to pay taxes to Caesar, he’ll offend the Herodians, who work hand-in-hand with the Romans and who will, no doubt, report him to the imperial authorities, who will not be amused. Either way, he’s trapped. Whatever comes out of his mouth, it seems he loses.

Instead, Jesus asks them to show him a coin, one that is used for the temple tax. A silver denarius and to tell him whose likeness and title it bears. Now, in those days, a denarius featured the head of Tiberius Caesar, along with an inscription that read: “Tiberius Caesar, Son of the Divine Augustus, Augustus.” From a Jewish point of view, that coin was a graven image (a violation of one of the Ten Commandments—no small thing) and a bite-sized bit of blasphemy to boot. Notice how Jesus asks for the denarius. He doesn’t have one. In fact, if you think about it—no seriously devout Jew would, certainly not within the temple confines. But the religious leaders opposing him do—and their casual production of a blasphemous coin within the Temple grounds is something of a damning act in and of itself.

Jesus asks: “Whose image is on that coin?” “The emperor’s,” they respond. And then comes Jesus’ remarkable answer: “Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” In effect, what Jesus is saying is this: “Give the emperor his due—and, by the same token, do the same for God! Give the emperor the things that bear his image—and tell me, what bear’s God’s image? Human beings, of course. Our whole lives should be “given” to God in the sense of participating in the mission of God, following God’s law, doing justice, loving kindness and walking humbly with the Giver of all good things.

You see, Jesus here isn’t dividing the world into separate camps of “spiritual” and “Political”. He’s pointing out that “spiritual” is a much, much bigger category than we might have thought.

David Lose writes: “Several years ago, one of the pastors of the congregation we attended in Minneapolis put a number of markers in the pews one Sunday morning and after reminding us that all we have and are belongs to God—and that all God has and is, is also ours!—she invited us to mark one of our credit cards with the sign of the cross. I did that, and for the next several months it was nearly impossible to buy something and not reflect on whether or not this purchase aligned with my own sense of values and God-given identity….I had to think for myself about how my faith impacted my decisions about spending. And it wasn’t a burden. In fact, it was rather empowering to be reminded of my identity as a child of God, something no amount of spending or saving could change. What it did was root me in my faith and invite me to actively reflect on how my faith shaped my daily life and particularly my economic life.”

If you were to condense this Gospel reading down to it elemental nature. What Jesus said could be translated this way: “The coin. It’s only money. Give God your heart.” The encounter between Jesus, the Pharisees and the Herodians—it’s more than a game of words. Indeed, there’s a challenge implicit in this reading for all of us here. This lesson gives us an opportunity to consider what we believe—about ourselves, about God, and our place in this world and a challenge to think deeply upon what we owe and to whom, and how we might offer ourselves in joy and with thanksgiving to the Lord of Love. In Jesus’ name. Amen.